Si Mabuti

by Genoveva Edroza-Matute

Hindi ko siya nakikita ngayon. Ngunit sinasabi nilang naroroon pa siya sa dating pinagtuturuan, sa walang pintang paaralang una kong kinakitaan ng sa kanya. Sa isa sa mga lumang silid sa ikalawang palapag, sa itaas ng lumang hagdang umiingit sa bawat hakbang, doon sa kung manunungawaymatatanaw ang maitim na tubig ng isang estero. Naroon pa siya't nagtuturo ng mga kaalamang pang-aklat, at bumubuhay ng isang uri ng karunungang sa kanya ko lamang natutuhan. Lagi ko siyang inuugnay sa kariktan ng buhay. Saan man sa kagandahan; sa tanawin, sa isang isipan o sa isang tunog kaya, nakikita ko siya at ako'y lumiligaya. Ngunit walang anumang maganda sa kanyang anyo. at sa kanyang buhay. Siya ay isa sa mga pangkaraniwang guro noon. Walang sinumang nag-ukol sa kanya ng pansin. Mula sa pananamit hanggang sa paraan ng pagdadala niya ng mga pananagutan sa paaralan, walang masasabing anumang pangkaraniwan sa kanya. Siya'y tinatawag naming lahat na si Mabuti kung siya'y nakatalikod. Ang salitang iyon ang simula ng halos lahat ng kanyang pagsasalita. Iyon ang mga pumalit sa mga salitang hindi niya maalala kung minsan, at nagiging pamuno sa mga sandaling pag-aalanganin. Sa isang paraang alirip, iyon ay nagiging salaminan ng uri ng paniniwala sa buhay. "Mabuti," ang sasabihin niya, "ngayo'y magsisimula tayo sa araling ito. Mabuti nama't umabot tayo sa bahaging ito. Mabuti, Mabuti!" Hindi ako kailanman magtatapat sa kanya ng anuman kung di lamang nahuli niya akong lumuluha nang hapong iyon, iniluha ng bata kong puso ang pambata ring suliranin. Noo'y magtatakip-silim na at maliban sa pabugso-bugsong hiyawan ng mga nagsisipanoodsapagsasanay ng mga manlalaro ng paaralan, ang buong paligid ay tahimik na. Sa isang tagong sulok ng silid-aklatan,pinilit kong lutasin ang aking suliranin sa pagluha. Doon niya ako natagpuan. "Mabuti't may tao pala rito," wika niyang ikinukubli ang pag-aagam-agam sa narinig. "Tila may suliranin, mabuti sana kung makakatulong ako." Ibig kong tumakas sa kanya at huwag nang bumalik pakailanman. Sa bata kong isipan, ay ibinilang kong kahihiyan at kababaan ang pagkikita pa namingmuli sa hinaharap, pagkikitang magbabalik sa gunita ng hapong iyon. Ngunit, hindi ako makakilos sasinabi niya pagkatapos. Napatda ako na napaupong bigla sa katapat na luklukan. "Hindi ko alam namay tao rito . . . naparito ako upang umiyak din." Hindi ako nakapangusap sa katapatang naulinig ko sa kanyang tinig. Nakababa ang kanyang paningin sa aking kandungan. Maya-maya pa'y nakitako ang bahagyang ngiti sa kanyang labi. Tinanganan niya ang aking mga kamay at narinig ko na lamang ang tinig sa pagtatapat sa suliraning sa palagay ko noo'y siyang pinakamabigat. Nakinig siya sa akin, at ngayon, sa paglingon ko sa pangyayaring iyo'y nagtataka ako kung paanong napigil niyaangpaghalakhak sa gayong kamusmos na bagay. Ngunit siya'y nakinig nang buong pagkaunawa, at alam ko na ang pagmamalasakit niya'y tunay na matapat. Lumabas kaming magkasabay sa paaralan. Ang panukalang naghihiwalay sa amin ay natatanaw na ng bigla kong makaalala. "Siya nga pala, Ma'am, kayo? Kayo nga pala? Ano ho iyong ipinunta ninyo sa sulok na iyon na iniiyakan ko?" Tumawa siya nang marahan at inulit ang mga salitang iyon; "ang sulok na iyon na . . . iniiyakan natin. . . nating dalawa." Nawala ang marahang halakhak sa kanyang tinig: "Sana'y masabi ko sa iyo, ngunit ang suliranin. . . kailanman. Ang ibig kong sabihin ay . . . maging higit na mabuti sana sa iyo ang. . .buhay." Si Mabuti'y naging isang bagong nilikha sa akin mula nang araw na iyon. Sa pagsasalita niya mulasahapag, pagtatanong, sumagot, sa pagngiti niyang mabagal at mahihiyain niyang mga ngiti sa amin, sapagkalim ng kunot sa noo niya sa kanyang pagkayamot, naririnig kong muli ang mga yabag na palapit sa sulok na iyon ng silid-aklatan. Ang sulok na iyon. . . "Iniiyakan natin," ang sinabi niya nanghapong iyon. At habang tumataginting sa silid namin ang kanyang tinig sa pagtuturo'y hinuhulaan ko ang dahilan o mga dahilan ng pagtungo niya sa sulok na iyon ng silid-aklatan. Hinuhulaan ko kung nagtutungo pa siya roon, sa aming sulok na iyong. . . aming dalawa. At sapagkat natuklasan ko ang katotohanang iyon tungkol sa kanya, nagsimula akong magmasid, maghintay ng mga bakas ng kapaitan sa kanyang mga sinasabi. Ngunit, sa tuwina, kasayahan, pananalig, pag-asa ang taglay niya sa aming silid-aralan. Pinuno nya ng maririkit na guni-guni an gaming isipan at ng mga tunog ang aming mga pandinig at natutuhan naming unti-unti ang kagandahan ng buhay. Bawat aralin namin sa panitikan ay naging isang pagtighaw sa kauhawan naming sa kagandahan at ako'y humanga. Wala iyon doon kanina, ang masasabi ko sa aking sarili pagkatapos na maipadamaniya sa amin ang kagandahan ng buhay sa aming aralin. At hindi naging akin ang pagtuklas na ito sa kariktan kundi pagkatapos lamang ng pangyayaring iyon sa silid-aklatan. Ang pananalig niya sa kalooban ng Maykapal, sa sangkatauhan, sa lahat na, isa sa mga pinakamatibay na aking nakilala. Nakasasaling ng damdamin. Marahil, ang pananalig niyang iyon ang nagpakita sa kanyang kagandahan sa mga bagay na karaniwan na lamang sa amin ay walang kabuluhan. Hindi siyabumabanggit ng anuman tungkol sa kanyang sarili sa buong panahon ng pag-aaral namin sa kanya, Ngunit bumabanggit siya tungkol sa kanyang anak na babae, sa tangi niyang anak. . . nang paulit-ulit. Hindi rin siya bumabanggit sa amin kailanman tungkol sa ama ng batang iyon. Ngunit, dalawa samgakamag-aral namin ang nakababatid na siya'y hindi balo. Walang pag-aalinlangan ang lahat ng bagay at pangarap niyang maririkit ay nakapaligid sa batang iyon. Isinalaysay niya sa amin ang katabilanniyon. Ang paglaki ng mga pangarap niyon, ang nabubuong layunin niyon niyang baka siya ay hindi umabot sa matatayog na pangarap ng kanyang anak. Maliban sa iilan sa aming pangkat, paulit-ulit niyang pagbanggit sa kanyang anak ay iisa lamang sa mga bagay na "pinagtitiisang" pakinggan sapagkat walang paraang maiwasan iyon. Sa akin, ang bawat pagbanggit niyon ay nagkakaroon ng kahulugan sapagkat noon pa man ay nabubuo na sa aking isipan ang isang hinala. Sa kanyang magandang salaysay, ay nalalaman ang tungkol sa kaarawan ng kanyang anak, ang bagong kasuotan niyong may malaking lasong pula sa baywang, ang mga kaibigan niyong mga batarin, ang kanilang mga handog. Ang anak niya'y anim na taong gulang na. Sa susunod na taon niya'y magsisimula na iyong mag-aral. At ibig ng guro naming maging manggagamot ang kanyang anakat isang mabuting manggagamot. Nasa bahaging iyon ang pagsasalita ng aming guro nang isang bata sa aking likuran ang bumulong: "Gaya ng kanyang ama!" Narinig ng aming guro ang sinabing iyon ng batang lalaki. At siya'y nagsalita. "Oo, gaya ng kanyang ama," ang wika niya. Ngunit tumakas ang dugo sa kanyang mukha habang sumisilay ang isang pilit na ngiti sa kanyang labi. Iyon angunaat huling pagbanggit sa aming klase ang tungkol sa ama ng batang may kaarawan. Matitiyak ko noong may isang bagay ngang mali siya sa buhay niya. Mali siya nang ganoon na lamang. At habang nakaupo ako sa aking luklukan, may dalawang dipa lamang ang layo sa kanya, kumirot ang puso ko sa pagnanasang lumapit sa kanya, tanganan ang kanyang mga kamay gaya ng ginawa niya nang hapong iyon sa sulok ng silid-aklatan, at hilinging magbukas ng dibdib sa akin. Marahil, makagagaan sa kanyang damdamin kung may mapagtatapatan siyang isang tao man lamang. Ngunit, ito ang sumupil sa pagnanasa kong yaon; ang mga kamag-aral kong nakikinig ng walang anumang malasakit sa kanyang sinasabing, "Oo, gaya ng kanyang ama," habang tumatakas ang dugo sa kanyang mukha. Pagkatapos, may sinabi siyang hindi ko makakalimutan kailanman. Tiningnanniyaako ng buong tapang na pinipigil ang pagnginig ng mga labi at sinabi ang ganito: "Mabuti.. mabuti gaya ng sasabihin nitong iyon lamang nakararanas ng mga lihim na kalungkutan ang maaaring makakilala ng mga lihim na kaligayahan." "Mabuti, at ngayon, magsimula sa ating aralin". Natiyak ko noon, gaya ng pagkakatiyak ko ngayon na hindi akin ang pangungusap na iyon, nadama kong siya at ako ay iisa. At kami ay bahagi ng mga nilalang na sapagkat nakaranas ng mga lihim na kalungkutan ay nakakilala ng mga lihim na kaligayahan. At minsan pa, nang umagang iyon, habang unti-unting bumabalik ang dating kulay ng mukha niya, muli niyang ipinamalas sa amin ang mga natatagong kagandahan sa aralin namin sa panitikan. Ang kariktan ng katapangan; ang kariktan ng pagpapatuloy anuman ang kulay ng buhay. At ngayon, ilang araw lamang ang nakararaan buhat nang mabalitaan ko ang tungkol sa pagpanawngmanggagamot na iyon. Ang ama ng batang iyon marahil ay magiging isang manggagamot din balang araw, ay namatay at naburol ng dalawang gabi at dalawang araw sa isang bahay na hindi siyang tirahan ni Mabuti at ng kanyang anak. At naunawaan ko ang lahat. Sa hubad na katotohanan niyo at sa buong kalupitan niyon ay naunawaan ko ang lahat.

Tata Selo

by Rogelio Sikat

Maliit lamang sa simula ang kalumpon ng taong nasa bakuran ng munisipyo, ngunit ng tumaas angaraw, at kumalat na ang balitang tinaga at napatay si Kabesang Tano, ay napuno na ang bakuranngbahay-pamahalaan.

Naggitgitan ang mga tao, nagsiksikan, nagtutulakan, bawat isa’y naghahangan makalapit sa istaked.

“Totoo ba, Tata Selo?” “Binawi niya ang aking saka kaya tinaga ko siya.” Nasa loob ng istaked si Tata Selo. Mahigpit na nakahawak sa rehas. May nakaalsang putok sa noo. Nakasungaw ang luha sa malaboat tila lagi nang may inaaninawna mata. Kupas ang gris niyangsuot, may mga tagpi na ang sikoat paypay. Ang kutod niyang yari sa matibay na supot ng asin aymay bahid ng natuyong putik. Nasa harap niya at kausap angisang magbubukid ang kanyang kahangga, na isa sa nakalusot sa mga pulis na sumasawatasa nagkakagulong tao. “Hindi ko ho mapaniwalaan, Tata Selo,” umiiling na wika ng kanyang kahangga, “talaganghindi ko ho mapaniwalaan.” Hinaplus-haplos ni tata Seloang ga-daliri at natuyuan na ng dugong putok sa noo. Sa kanyang harapan, di kalayuan sa istaked, ipinagtitilakan ng mga pulis ang mga taong ibig makakita sa kanya. Mainit ang Sikat ng araw na tumatama sa mga ito, walanghumihihip na hangin at sa kanilang ulunan ay nakalutang ang nagsasalisod na alikabok.

“Bakit niya babawiin ang saka?” tanong ng Tata Selo. “Dinaya ko na ba siya sa partihan? Tinusokona ba siya? Siya ang may-ari ng lupa at kasama lang niya ako. Hindi ba’t kaya maraming nagagalit saakin ay dahil sa ayaw kong magpamigay ng kahit isang pinangko kung anihan?”Hndi pa rin umalis sa harap ng istaked si Tata Selo. Nakahawak pa rin siya sa rehas. Nakatinginsiyasa labas ngunit wala siyang sino mang tinitingnan. Hindi mo na sana tinaga ang Kabesa,” anang binatang anak ng pinakamayamang propitaryosaSanRoque, na tila isang magilas na pinunong bayan nakalalahad sa pagitan ng maraming tao sa istaked. Mataas ito, maputi, nakasalaming may kulay, at nakapamaywang habang naninigarilyo. “Binabawi po niya ang aking saka,” sumbong ni Tata Selo. “Saan pa po ako pupunta kung walanaakong saka?”

Kumumpas ang binatang mayaman. “Hindi katwiran iyan para tagain mo ang Kabesa. Ari niyaanglupang sinasaka mo. Kung gusto ka niyang paalisin, mapapaalis ka niya anumang oras.”Halos lumabas ang mukha ni Tata Selo sa rehas. “Ako po’y hindi ninyo nauunawaan,” nakatingala at nagpipilit ngumiting wika niya sa binatang nagtapon ng sigarilyo at mariing tinapakan pagkatapos. “alam po ba ninyong dating amin anglupangiyon? Naisangla lamang po nang magkasakit ang aking asawa, naembargo lamang po ng Kabesa. Pangarap ko pong bawiin ang lupang iyon kaya nga po ako hindi nagbibigay ng kahit isang pinangkokung anihan. Kung hindi ko na naman po mababawi, masasaka man lamang po.nakikiusap poakosaKabesa kangina. ‘kung maaari po sana, ‘Besa’’, wika ko po, ‘kung maaari po sana, huwag namanponinyo akong paalisin. Kaya ko pa pong magsaka, ‘Besa. Totoo pong ako’y matanda na, ngunit akopanama’y malakas pa.’ Ngunit…Ay! Tinungkod po niya ako nang tinungkod, Tingnan po n’yongputoksa aking noo, tingnan po ‘nyo.” Dumukot ng sigarilyo ang binata. Nagsindi ito at pagkaraa’y tinalikuran si Tata Selo at lumapit saisang pulis. “Pa’no po ba’ng nangyari, Tata Selo?” Sa pagkakahawak sa rehas, napabaling si Tata Selo. Nakita niya ang isang batang magbubukidnanakalapit sa istaked. Nangiti si Tata Selo. Narito ang isang magbubukid, anak-magbubukidnananiniwala sa kanya. Nakataas ang malapad na sumbrerong balanggot ng bata.

Nangungulintab ito, ang mga bisig at binti ay may halas. May sukbit itonglilik. “Pinuntahan niya ako sa aking saka, amang,” paliwanag ni Tata Selo. “Doon ba sa may sangka. Pinaalis ako sa aking saka, ang wika’y iba na raw ang magsasaka. Nang makiusap ako’y tinungkodako. Ay! Tinungkod ako, amang, nakikiusap ako sapagkat kung mawawalan ako ng saka ay saanpaako pupunta?” “Wala na nga kayong mapupuntahan, Tata Selo.” Gumapang ang luha sa pisngi ni Tata Selo. Tahimik na nakatingin sa kanya angbata. “Patay po ba?” Namuti ang mga kamao ni Tata Selo sa pagkakahawak sa rehas. Napadukmo siya sa balikat. “Pa’no po niyan si Saling?” muling tanong ng bata. Tinutukoy nito ang maglalabimpitong anakni Tata Selo na ulila na sa ina. Katulong ito kina Kabesang Tano at kamakalawa lamang umuwi kay Tata Selo. “Pa’no po niyansi Saling?” Lalong humigpit ang pagkakahawak ni Tata Selo sa rehas. Hindi pa nakakausap ng alkalde si TataSelo. Mag-aalas-onse na nang dumating ito, kasama ang hepe ng pulis. Galing sila sa bahay ngkabesa. Abut-abot ang busina ng dyip na kinasaksakyan ng dalawang upang mahawi ang hanggang noo’ydi pa nag-aalisang tao. Tumigil ang dyip sa di-kalayuan sa istaked. “Patay po ba? Saan po ang taga?” Naggitgitan at nagsiksikan ang mga pinagpawisang tao. Itinaas ng may-katabaang alkaldeangdalawang kamay upang payapain ang pagkakaingay. Nanulak ang malaking lalakinghepe. “Saan po tinamaan?” “Sa bibig.” Ipinasok ng alkalde ang kanang palad sa bibig, hinugot iyon at mariing ihinagodhanggang sa kanang punog tainga. “Lagas ang ngipin.” Nagkagulo ang mga tao. Nagsigawan, nagsiksikan, naggitgitan, nagtulakan. Nanghatawng batutaangmga pulis. Ipinasya ng alkalde na ipalabas ng istaked si Tata Selo at dalhin sa kanyang tanggapan. Dalawang pulis ang kumuha kay Tata Selo sa istaked. “Mabibilanggo ka niyan, Tata Selo,” anang alkalde pagkapasok ni Tata Selo. Umupo si Tata Selosasilyang nasa harap ng mesa. Nanginginig ang kamay ni Tata Selo nang ipatong niya iyonsanasasalaminang mesa. “Pa’no nga ba’ng nangyari?” kunot at galit na tanong ng alkalde. Matagal bago nakasagot si Tata Selo. “Binawi po niya ang aking saka, Presidente,” wika ni Tata Selo. “Ayaw ko pong umalis doon. Dati pong amin ang lupang iyon, amin, po, Naisangla lamang po at naembargo—“ “Alam ko na iyan,” kumukupas at umiiling na putol ng nabubugnot na alkalde. Lumunok si Tata Selo. Nang muli siyang tumingin sa presidente, may nakasungawnang luhasakanyang malalabo at tila lagi nang may inaaninaw na mata. “Ako po naman, Presidente, ay malakas pa,” wika ni Tata Selo. “Kaya ko pa pong magsaka. Makatuwiran po bang paalisin ako? Malakas pa po naman ako, Presidente, malakas pa po.” “Saan mo tinaga ang Kabesa?” Matagal bago nakasagot si Tata Selo. “Nasa may sangka po ako nang dumating ang Kabesa. Nagtatapal po ako ng pitas na pilapil. Alamkopong pinanonood ako ng kabesa, kung kaya po naman pinagbuti ko ang paggawa, para malamanniyang ako po’y talagang malakas pa, kaya ko pa pong magsaka. Walang anu-ano po, tinawagniyaako at nang ako po’y lumapit, sinabi niyang makakaalis na ako sa aking saka sapagkat iba naangmagsasaka. ‘Bakit po naman, ‘Besa?’ tanong ko po. Ang wika’y umalis na lang daw po ako. ‘Bakit po naman, ‘Besa?’ Tanong ko po uli, ‘malakas pa po naman ako, a’ Nilapitan po niya ako. Nakiusap pa poakosa kanya, ngunit ako po’y… Ay! Tinungkod po niya ako ng tinungkod nang tinungkod.” “Tinaga mo na no’n,” anag nakamatyag na hepe. Tahimik sa tanggapan ng alkalde. Lahat ng tingin—may mga eskribante pang nakapasok doon—aynakatuon kay Tata Selo. Nakayuko si Tata Selo at gagalaw-galaw ang tila mamad na daliri sa ibabawng maruming kutod. Sa pagkakatapak sa makintab na sahig, hindi mapalagay ang kanyang mayputik, maalikabok at luyang paa. “Ang iyong anak, na kina Kabesa raw?” usisa ng alkalde. Hindi sumagot si Tata Selo. “Tinatanong ka anang hepe.” Lumunok si Tata Selo. “Umuwi na po si Saling, Presidente.” “Kailan?” “Kamakalawa po ng umaga.” “Di ba’t kinakatulong siya ro’n?” “Tatlong buwan na po.” “Bakit siya umuwi?” Dahan-dahang umangat ang mukha ni Tata Selo. Naiiyak na napayuko siya. “May sakit po siya.” Nang sumapit ang alas-dose—inihudyat iyon ng sunod-sunod na pagtugtog ng kampana sa simbahanna katapat lamang ng munisipyo—ay umalis ang alkalde upang mananghalian. Naiwan si Tata Selo, kasama ang hepe at dalawang pulis. “Napatay mo pala ang kabesa,” anang malaking lalaking hepe. Lumapit ito kay Tata SelonaNakayuko at di pa natitinag sa upuan. “Binabawi po niya ang aking saka.” Katwiran ni Tata Selo. Sinapo ng hepe si Tata Selo. Sa lapaghalos mangudngod si Tata Selo. “Tinungkod po niya ako ng tinungkod,” nakatingala, umiiyak at kumikinig ang labing katwiranni Tata Selo. Itinayo ng hepe si Tata Selo. Kinadyot ng hepe si Tata Selo sa sikmura. Sa sahig napaluhodsi Tata Selo, nakakapit sa uniporment kaki ng hepe. “Tinungkod po niya ako ng tinungkod… Ay! Tinungkod po niya ako ng tinungkod ng tinungkod…”Sa may pinto ng tanggapan, naaawang nakatingin ang dalawang pulis. “Si Kabesa kasi ang nagrekomenda kay Tsip, e,” sinabi ng isa nang si Tata Selo ay tila damit nanalaglag sa pagkakasabit nang muling pagmalupitan ng hepe. Mapula ang sumikat na araw kinabukasan. Sa bakuran ng munisipyo nagkalat ang papel na naiwannang nagdaang araw. Hindi pa namamatay ang alikabok, gayong sa pagdating ng buwang iyo’y dapat nang nag-uuulan. Kung may humihihip na hangin, may mumunting ipu-ipong nagkakalat ng mga papel sa itaas. “Dadalhin ka siguro sa kabesera, Selo,” anang bagong paligo at bagong bihis na alkalde sa matandang nasa loob ng istaked. “Don ka suguro ikukulong.”

Wala ni papag sa loob ng istaked at sa maruming sementadong lapag nakasalampak si Tata Selo. Sapaligid niya’y natutuyong tamak-tamak na tubig. Naka-unat ang kanyang maiitimat hinahalas napaaat nakatukod ang kanyang tila walang butong mga kamay. Nakakiling, naka-sandal siya sa steel matting na siyang panlikurang dingding ng istaked. Sa malapit sa kanyang kamay, hindi na gagalawang sartin ng maiitim na kape at isang losang kanin. Nilalangawiyon. “Habang-buhay siguro ang ibibigay sa iyo,” patuloy ng alkalde. Nagsindi ito ng tabako at lumapit saistaked. Makintab ang sapatos ng alkalde. “Patayin na rin ninyo ako, Presidente.” Paos at bahagya nang narinig si Tata Selo. Napatay kopoangKabesa. Patayin na rin ninyo po ako.” Takot humipo sa maalikabok na rehas ang alkalde. Hindi niya nahipo ang rehas ngunit pinagkiskisniya ng mga palad at tiningnan niya kung may alikabok iyon. Nang tingnan niya si Tata Selo, nakitaniyang lalo nang nakiling ito. May mga tao namang dumarating sa munisipyo. Kakaunti lang iyon kaysa kahapon. Nakapasokangmga iyon sa bakuran ng munisipyo, ngunit may kasunod na pulis. Kakaunti ang magbubukidsabagong langkay na dumating at titingin kay Tata Selo. Karamihan ay taga-Poblacion. Hanggangnoon, bawat isa’y nagtataka, hindi makapaniwala, gayong kalat na ang balitang ililibing kinahapunanangKabesa. Nagtataka at hindi makapaniwalang nakatingin sila kay Tata Selo na tila isangdi pangkaraniwang hayop na itatanghal. Ang araw, katulad kahapon, ay mainit na naman. Nang magdadakong alas-dos, dumating ang anakni Tata Selo. Pagkakita sa lugmok na ama, mahigpit itong napahawak sa rehas at malakas nahumagulgol. Nalaman ng alkalde na dumating si Saling at ito’y ipinatawag sa kanyang tanggapan. Di-nagtagal at si Tata Selo naman ang ipinakaon. Dalawang pulis ang umalalay kay Tata Selo. Halosbuhatan siyang dalawang pulis. Pagdating sa bungad ng tanggapan ay tila saglit na nagkaroon ng lakad si Tata Selo. Nakita niyaangbabaing nakaupo sa harap ng mesa ng presidente. Nagyakap ang mag-ama pagkakita. “Hindi ka na sana naparito Saling,” wika ni Tata Selo na napaluhod. “May sakit ka, Saling, maysakit ka!” Tila tulala ang anak ni Tata Selo habang kalong ang ama. Nakalugay ang walang kintab niyangbuhok, ang damit na suot ay tila yaong suot pa nang nagdaang araw. Matigas ang kanyang namumulangmukha. Pinalipat-lipat niya ang tingin mula sa nakaupong alkalde hanggang sa mga nakatingingpulis. “Umuwi ka na, Saling” hiling ni Tata Selo. “Bayaan mo na…bayaan mo na. Umuwi ka na, anak. Huwag, huwag ka nang magsasabi…” Tuluyan nang nalungayngay si Tata Selo. Ipinabalik siya ng alkalde sa istaked. Pagkabalik niyasaistaked, pinanood na naman siya ng mga tao. “Kinabog kagabi,” wika ng isang magbubukid. “Binalutan ng basang sako, hindi ng halata.”

“Ang anak, dumating daw?” “Naki-mayor.” Sa isang sulok ng istaked iniupo ng dalawang pulis si Tata Selo. Napasubsob si Tata Selo pagkaraang siya’y maiupo. Ngunit nang marinig niyang muling ipinanakaw ang pintong bakal ng istaked, humihilahod na ginapang niya ang rehas. Mahigpit na humawak doon at habang nakadapa’y ilang sandali ring iyo’y tila huhutukin. Tinawag siya ng mga pulis ngunit paos siya at malayo na ang mga pulis. Nakalabas ang kanang kamay sa rehas, bumagsak ang kanyang mukha sa sementadonglapag. Matagal siyang nakadapa bago niya narinig na may tila gumigising sa kanya. “Tata Selo…Tata Selo…” Umangat ang mukha ni Tata Selo. Inaninaw ng mga luha niyang mata ang tumatawag sa kanya. Iyon ang batang dumalaw sa kanya kahapon. Hinawakan ng bata ang kamay ni Tata Selo na umabot sa kanya. “Nando’n amang si Saling sa Presidente,” wika ni Tata Selo. “Yayain mo nang umuwi, umuwi nakayo.” Muling bumagsak ang kanyang mukha sa lapag. Ang bata’y saglit na nag-paulik-ulik, pagkaraa’y takot at bantulot nang sumunod… Mag-iikaapat na ng hapon. Padahilig na ang sikat ng araw, ngunit mainit pa rin iyon. May kapirasonang lihin sa istaked, sa may dingding na steel matting, ngunit si Tata Selo’y wala roon. Nasa init siya, nakakapit sa rehas sa dakong harapan ng istaked. Nakatingin siya sa labas, sa kanyang malalaboat tila lagi nang nag-aaninaw na mata’y tumatama ang mapulang sikat ng araw. Sa labas ng istaked, nakasandig sa rehas ang batang Inutusan niya kanina. Sinabi ng bata na ayaw siyang papasukinsatanggapan ng alkalde ngunit hindi siya pinakinggan ni Tata Selo, na ngayo’y hindi pagbawi ngsakaang sinasabi. Habang nakakapit sa rehas at nakatingin sa labas, sinasabi niyang lahat ay kinuha na sa kanila, lahat, ay! Ang lahat ay kinuha na sa kanila…

Morning in Nagrebcan

by Manuel E. Arguilla

It was sunrise at Nagrebcan. The fine, bluish mist, low over the tobacco fields, was lifting and thinning moment by moment. A ragged strip of mist, pulled away by the morning breeze, had caught on the clumps of bamboo along the banks of the stream that flowed to one side of the barrio. Before long the sun would top the Katayaghan hills, but as yet no people were around. In the grey shadow of the hills, the barrio was gradually awaking. Roosters crowed and strutted on the ground while hens hesitated on their perches among the branches of the camanchile trees. Stray goats nibbled the weeds on the sides of the road, and the bull carabaos tugged restively against their stakes.

In the early morning the puppies lay curled up together between their mother’s paws under the ladder of the house. Four puppies were all white like the mother. They had pink noses and pink eyelids and pink mouths. The skin between their toes and on the inside of their large, limp ears was pink. They had short sleek hair, for the mother licked them often. The fifth puppy lay across the mother’s neck. On the puppy’s back was a big black spot like a saddle. The tips of its ears were black and so was a patch of hair on its chest.

The opening of the sawali door, its uneven bottom dragging noisily against the bamboo flooring, aroused the mother dog and she got up and stretched and shook herself, scattering dust and loose white hair. A rank doggy smell rose in the cool morning air. She took a quick leap forward, clearing the puppies which had begun to whine about her, wanting to suckle. She trotted away and disappeared beyond the house of a neighbor.

The puppies sat back on their rumps, whining. After a little while they lay down and went back to sleep, the black-spotted puppy on top.

Baldo stood at the threshold and rubbed his sleep-heavy eyes with his fists. He must have been about ten years old, small for his age, but compactly built, and he stood straight on his bony legs. He wore one of his father’s discarded cotton undershirts.

The boy descended the ladder, leaning heavily on the single bamboo railing that served as a banister. He sat on the lowest step of the ladder, yawning and rubbing his eyes one after the other. Bending down, he reached between his legs for the black-spotted puppy. He held it to him, stroking its soft, warm body. He blew on its nose. The puppy stuck out a small red tongue, lapping the air. It whined eagerly. Baldo laughed a low gurgle.

He rubbed his face against that of the dog. He said softly, “My puppy. My puppy.” He said it many times. The puppy licked his ears, his cheeks. When it licked his mouth, Baldo straightened up, raised the puppy on a level with his eyes. “You are a foolish puppy,” he said, laughing. “Foolish, foolish, foolish,” he said, rolling the puppy on his lap so that it howled.

The four other puppies awoke and came scrambling about Baldo’s legs. He put down the black-spotted puppy and ran to the narrow foot bridge of woven split-bamboo spanning the roadside ditch. When it rained, water from the roadway flowed under the makeshift bridge, but it had not rained for a long time and the ground was dry and sandy. Baldo sat on the bridge, digging his bare feet into the sand, feeling the cool particles escaping between his toes. He whistled, a toneless whistle with a curious trilling to it produced by placing the tongue against the lower teeth and then curving it up and down.

The whistle excited the puppies; they ran to the boy as fast as their unsteady legs could carry them, barking choppy little barks.

Nana Elang, the mother of Baldo, now appeared in the doorway with handful of rice straw. She called Baldo and told him to get some live coals from their neighbor.

“Get two or three burning coals and bring them home on the rice straw,” she said. “Do not wave the straw in the wind. If you do, it will catch fire before you get home.” She watched him run toward Ka Ikao’s house where already smoke was rising through the nipa roofing into the misty air. One or two empty carromatas drawn by sleepy little ponies rattled along the pebbly street, bound for the railroad station.

Nana Elang must have been thirty, but she looked at least fifty. She was a thin, wispy woman, with bony hands and arms. She had scanty, straight, graying hair which she gathered behind her head in a small, tight knot. It made her look thinner than ever. Her cheekbones seemed on the point of bursting through the dry, yellowish-brown skin. Above a gray-checkered skirt, she wore a single wide-sleeved cotton blouse that ended below her flat breasts. Sometimes when she stooped or reached up for anything, a glimpse of the flesh at her waist showed in a dark, purplish band where the skirt had been tied so often.

She turned from the doorway into the small, untidy kitchen. She washed the rice and put it in a pot which she placed on the cold stove. She made ready the other pot for the mess of vegetables and dried fish. When Baldo came back with the rice straw and burning coals, she told him to start a fire in the stove, while she cut the ampalaya tendrils and sliced the eggplants. When the fire finally flamed inside the clay stove, Baldo’s eyes were smarting from the smoke of the rice straw.

“There is the fire, mother,” he said. “Is father awake already?”

Nana Elang shook her head. Baldo went out slowly on tiptoe.

There were already many people going out. Several fishermen wearing coffee-colored shirts and trousers and hats made from the shell of white pumpkins passed by. The smoke of their home-made cigars floated behind them like shreds of the morning mist. Women carrying big empty baskets were going to the tobacco fields. They walked fast, talking among themselves. Each woman had gathered the loose folds of her skirt in front and, twisting the end two or three times, passed it between her legs, pulling it up at the back, and slipping it inside her waist. The women seemed to be wearing trousers that reached only to their knees and flared at the thighs.

Day was quickly growing older. The east flamed redly and Baldo called to his mother, “Look, mother, God also cooks his breakfast.”

He went to play with the puppies. He sat on the bridge and took them on his lap one by one. He searched for fleas which he crushed between his thumbnails. “You, puppy. You, puppy,” he murmured softly. When he held the black-spotted puppy, he said, “My puppy. My puppy.”

Ambo, his seven-year old brother, awoke crying. Nana Elang could be heard patiently calling him to the kitchen. Later he came down with a ripe banana in his hand. Ambo was almost as tall as his older brother and he had stout husky legs. Baldo often called him the son of an Igorot. The home-made cotton shirt he wore was variously stained. The pocket was torn, and it flipped down. He ate the banana without peeling it.

“You foolish boy, remove the skin,” Baldo said.

“I will not,” Ambo said. “It is not your banana.” He took a big bite and swallowed it with exaggerated relish. “But the skin is tart. It tastes bad.” “You are not eating it,” Ambo said. The rest of the banana vanished in his mouth.

He sat beside Baldo and both played with the puppies. The mother dog had not yet returned and the puppies were becoming hungry and restless. They sniffed the hands of Ambo, licked his fingers. They tried to scramble up his breast to lick his mouth, but he brushed them down. Baldo laughed. He held the black-spotted puppy closely, fondled it lovingly. “My puppy,” he said. “My puppy.” Ambo played with the other puppies, but he soon grew tired of them. He wanted the black-spotted one. He sidled close to Baldo and put out a hand to caress the puppy nestling contentedly in the crook of his brother’s arm. But Baldo struck the hand away. “Don’t touch my puppy,” he said. “My puppy.” Ambo begged to be allowed to hold the black-spotted puppy. But Baldo said he would not let him hold the black-spotted puppy because he would not peel the banana. Ambo then said that he would obey his older brother next time, for all time. Baldo would not believe him; he refused to let him touch the puppy.

Ambo rose to his feet. He looked longingly at the black-spotted puppy in Baldo’s arms. Suddenly he bent down and tried to snatch the puppy away. But Baldo sent him sprawling in the dust with a deft push. Ambo did not cry. He came up with a fistful of sand which he flung in his brother’s face. But as he started to run away, Baldo thrust out his leg and tripped him. In complete silence, Ambo slowly got up from the dust, getting to his feet with both hands full of sand which again he cast at his older brother. Baldo put down the puppy and leaped upon Ambo.

Seeing the black-spotted puppy waddling away, Ambo turned around and made a dive for it. Baldo saw his intention in time and both fell on the puppy which began to howl loudly, struggling to get away. Baldo cursed Ambo and screamed at him as they grappled and rolled in the sand. Ambo kicked and bit and scratched without a sound. He got hold of Baldo’s hair and ear and tugged with all his might. They rolled over and over and then Baldo was sitting on Ambo’s back, pummeling him with his fists. He accompanied every blow with a curse. “I hope you die, you little demon,” he said between sobs, for he was crying and he could hardly see. Ambo wriggled and struggled and tried to bite Baldo’s legs. Failing, he buried his face in the sand and howled lustily.

Baldo now left him and ran to the black-spotted puppy which he caught up in his arms, holding it against his throat. Ambo followed, crying out threats and curses. He grabbed the tail of the puppy and jerked hard. The puppy howled shrilly and Baldo let it go, but Ambo kept hold of the tail as the dog fell to the ground. It turned around and snapped at the hand holding its tail. Its sharp little teeth sank into the fleshy edge of Ambo’s palm. With a cry, Ambo snatched away his hand from the mouth of the enraged puppy. At that moment the window of the house facing the street was pushed violently open and the boys’ father, Tang Ciaco, looked out. He saw the blood from the toothmarks on Ambo’s hand. He called out inarticulately and the two brothers looked up in surprise and fear. Ambo hid his bitten hand behind him. Baldo stopped to pick up the black-spotted puppy, but Tang Ciaco shouted hoarsely to him not to touch the dog. At Tang Ciaco’s angry voice, the puppy had crouched back snarling, its pink lips drawn back, the hair on its back rising. “The dog has gone mad,” the man cried, coming down hurriedly. By the stove in the kitchen, he stopped to get a sizeable piece of firewood, throwing an angry look and a curse at Nana Elang for letting her sons play with the dogs. He removed a splinter or two, then hurried down the ladder, cursing in a loud angry voice. Nana Elang ran to the doorway and stood there silently fingering her skirt.

Baldo and Ambo awaited the coming of their father with fear written on their faces. Baldo hated his father as much as he feared him. He watched him now with half a mind to flee as Tang Ciaco approached with the piece of firewood held firmly in one hand. He is a big, gaunt man with thick bony wrists and stoop shoulders. A short-sleeved cotton shirt revealed his sinewy arms on which the blood-vessels stood out like roots. His short pants showed his bony-kneed, hard-muscled legs covered with black hair. He was a carpenter. He had come home drunk the night before. He was not a habitual drunkard, but now and then he drank great quantities of basi and came home and beat his wife and children. He would blame them for their hard life and poverty. “You are a prostitute,” he would roar at his wife, and as he beat his children, he would shout, “I will kill you both, you bastards.” If Nana Elang ventured to remonstrate, he would beat them harder and curse her for being an interfering whore. “I am king in my house,” he would say.

Now as he approached the two, Ambo cowered behind his elder brother. He held onto Baldo’s undershirt, keeping his wounded hand at his back, unable to remove his gaze from his father’s close-set, red-specked eyes. The puppy with a yelp slunk between Baldo’s legs. Baldo looked at the dog, avoiding his father’s eyes.

Tang Ciaco roared at them to get away from the dog: “Fools! Don’t you see it is mad?” Baldo laid a hand on Ambo as they moved back hastily. He wanted to tell his father it was not true, the dog was not mad, it was all Ambo’s fault, but his tongue refused to move. The puppy attempted to follow them, but Tang Ciaco caught it with a sweeping blow of the piece of firewood. The puppy was flung into the air. It rolled over once before it fell, howling weakly. Again the chunk of firewood descended, Tang Ciaco grunting with the effort he put into the blow, and the puppy ceased to howl. It lay on its side, feebly moving its jaws from which dark blood oozed. Once more Tang Ciaco raised his arm, but Baldo suddenly clung to it with both hands and begged him to stop. “Enough, father, enough. Don’t beat it anymore,” he entreated. Tears flowed down his upraised face.

Tang Ciaco shook him off with an oath. Baldo fell on his face in the dust. He did not rise, but cried and sobbed and tore his hair. The rays of the rising sun fell brightly upon him, turned to gold the dust that he raised with his kicking feet. Tang Ciaco dealt the battered puppy another blow and at last it lay limpy still. He kicked it over and watched for a sign of life. The puppy did not move where it lay twisted on its side. He turned his attention to Baldo. “Get up,” he said, hoarsely, pushing the boy with his foot.

Baldo was deaf. He went on crying and kicking in the dust. Tang Ciaco struck him with the piece of wood in his hand and again told him to get up. Baldo writhed and cried harder, clasping his hands over the back of his head. Tang Ciaco took hold of one of the boy’s arms and jerked him to his feet. Then he began to beat him, regardless of where the blows fell. Baldo encircled his head with his loose arm and strove to free himself, running around his father, plunging backward, ducking and twisting. “Shameless son of a whore,” Tang Ciaco roared. “Stand still, I’ll teach you to obey me.” He shortened his grip on the arm of Baldo and laid on his blows. Baldo fell to his knees, screaming for mercy. He called on his mother to help him. Nana Elang came down, but she hesitated at the foot of the ladder. Ambo ran to her. “You too,” Tang Ciaco cried, and struck at the fleeing Ambo. The piece of firewood caught him behind the knees and he fell on his face. Nana Elang ran to the fallen boy and picked him up, brushing his clothes with her hands to shake off the dust. Tang Ciaco pushed Baldo toward her. The boy tottered forward weakly, dazed and trembling. He had ceased to cry aloud, but he shook with hard, spasmodic sobs which he tried vainly to stop. “Here take your child,” Tang Ciaco said, thickly. He faced the curious students and neighbors who had gathered by the side of the road. He yelled at them to go away. He said it was none of their business if he killed his children. “They are mine,” he shouted. “I feed them and I can do anything I like with them.” The students ran hastily to school. The neighbors returned to their work.

Tang Ciaco went to the house, cursing in a loud voice. Passing the dead puppy, he picked it up by its hind legs and flung it away. The black and white body soared through the sunlit air; fell among the tall corn behind the house. Tang Ciaco, still cursing and grumbling, strode upstairs. He threw the chunk of firewood beside the stove. He squatted by the low table and began eating the breakfast his wife had prepared for him. Nana Elang knelt by her children and dusted their clothes. She passed her hand over the red welts on Baldo, but Baldo shook himself away. He was still trying to stop sobbing, wiping his tears away with his forearm. Nana Elang put one arm around Ambo. She sucked the wound in his hand. She was crying silently. When the mother of the puppies returned, she licked the remaining four by the small bridge of woven split bamboo. She lay down in the dust and suckled her young. She did not seem to miss the black-spotted puppy.

Afterward Baldo and Ambo searched among the tall corn for the body of the dead puppy. Tang Ciaco had gone to work and would not be back till nightfall. In the house, Nana Elang was busy washing the breakfast dishes. Later she came down and fed the mother dog. The two brothers were entirely hidden by the tall corn plants. As they moved about among the slender stalks, the corn-flowers shook agitatedly. Pollen scattered like gold dust in the sun, falling on the fuzzy· green leaves. When they found the dead dog, they buried it in one corner of the field. Baldo dug the grove with a sharp-pointed stake. Ambo stood silently by, holding the dead puppy. When Baldo finished his work, he and his brother gently placed the puppy in the hole. Then they covered the dog with soft earth and stamped on the grave until the disturbed ground was flat and hard again. With difficulty they rolled a big stone on top of the grave. Then Baldo wound an arm around the shoulders of Ambo and without a word they hurried up to the house.

The sun had risen high above the Katayaghan hills, and warm, golden sunlight filled Nagrebcan. The mist on the tobacco fields had completely dissolved.

Si Mabuti

by Genoveva Edroza-Matute

Reflection

"Si Mabuti" explores the complexities of human existence and the tremendous effects of knowing life beyond its outward appearances. The transformational power of true compassion is represented by the narrator's journey from disinterest to intense adoration for Mabuti. This progression emphasizes the value of avoiding making snap judgments about individuals based only on their looks, as well as the beauty of simplicity and humility in the face of the complexity of life.

The narrative eloquently illustrates how genuine compassion can overcome social and economic divides and expose the deep ties that bind us all as people. Finally, the narrator's transformation from disinterest to adoration serves as an example of the notion that true comprehension can only result from a more in-depth investigation of the human experience, highlighting the significance of seeing past the surface to uncover one's actual inner beauty. By doing this, "Kwento ni Mabuti" inspires us to develop compassion and empathy in our own lives by making us aware that every person, no matter how lowly, contains a universe of experiences and knowledge just waiting to be acknowledged.

Themes & Cultural Context

Beauty in Simplicity: The narrative emphasizes finding beauty in the ordinary and simple aspects of life, suggesting that profound meaning can be derived from seemingly mundane experiences.

Transformative Power of Care: Mabuti’s impact on the narrator’s life illustrates how genuine care and concern can be transformative, fostering a deeper understanding of oneself and others. .

Human Resilience: The story explores the resilience of the human spirit, emphasizing the capacity to find joy and meaning in the face of life’s challenges. .

Elements of Filipino culture may be inferred through the names of the characters and certain societal norms depicted in the narrative. The story may resonate more strongly with readers familiar with Filipino culture, but its universal themes make it relatable across cultural boundaries. .

Symbolism

The Corner of the Classroom: The corner of the classroom where Mabuti engages with the narrator symbolizes a safe space for emotional expression and the exploration of deeper truths. It becomes a symbolic sanctuary where vulnerabilities are shared and understood.

The Name “Mabuti”: The name Mabuti, meaning “good” or “well” in Filipino, serves as a constant reminder of the positive outlook and benevolent nature of the character. It symbolizes the innate goodness that exists within individuals.

Literary Techniques Used

Foreshadowing: The narrative employs foreshadowing, creating a sense of anticipation regarding Mabuti’s fate. This technique adds depth to the storytelling and invites readers to reflect on the impermanence of life.

Dialogue: The use of dialogue is significant in conveying the character of Mabuti and the evolving relationship between the teacher and the narrator. Through dialogue, the narrative captures the essence of Mabuti’s wisdom and compassion.

Imagery: Descriptive imagery is employed to paint a vivid picture of the surroundings, emotions, and interactions. This enhances the reader’s engagement and understanding of the characters and their environment.

Tata Selo

by Rogelio Sikat

Reflection

"Tata Selo" explores the complexities of rural life and captures both its simplicity and harshness. The author expertly transports readers to the heart of a Filipino barrio through vivid descriptions and astute observations, giving a vivid picture of the daily challenges and familial bonds that define the locals' lives. The narrative offers a glimpse into this community, where dependency, hard work, and subsistence farming are the norms. Tata Selo, the title character, personifies the resilience and steadfast devotion to his family. His everlasting devotion to his family is a reflection of the selflessness and tenacity present in many rural areas.

Readers are drawn into the story's unfolding tapestry of human emotions as they experience happy, angry, and loving moments. In the end, "Tata Selo" turns into a little representation of the broader rural Filipino experience, encouraging us to consider the timeless concepts of community, and the unbreakable human spirit.

Themes & Cultural Context

Land and Power: The central theme revolves around land ownership and its association with power. The struggles of Tata Seló highlight the inequality and exploitation faced by those who depend on the land for their livelihood.

Injustice: The narrative underscores the theme of injustice, as Tata Seló's actions are driven by a perceived violation of his rights. The legal and social systems seem inadequate in addressing his grievances, pushing him to a desperate act.

Generational Disparities: The presence of Saling, Tata Seló's daughter, adds a layer to the narrative, exploring how the younger generation perceives and deals with the issues their parents face. Saling's involvement with the authorities suggests a generational gap in handling societal problems.

Symbolism

Land plays a significant symbolic significance in the story, serving as a metaphor for lineage, identity, and way of life. The land is more than simply a physical location; it also reflects the lengthy cultural past and enduring values of the neighborhood to which it belongs. The loss of this piece of land serves as a symbol for a larger conflict in which the weak are pitted against the unrelenting flow of advancement and growth.

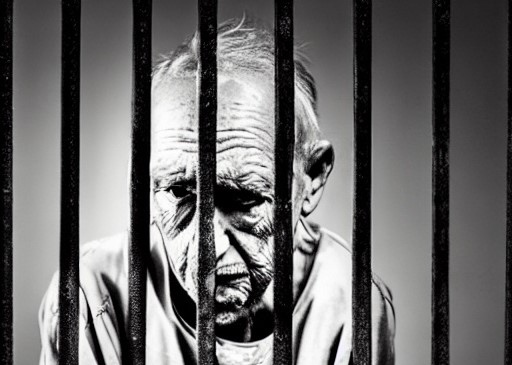

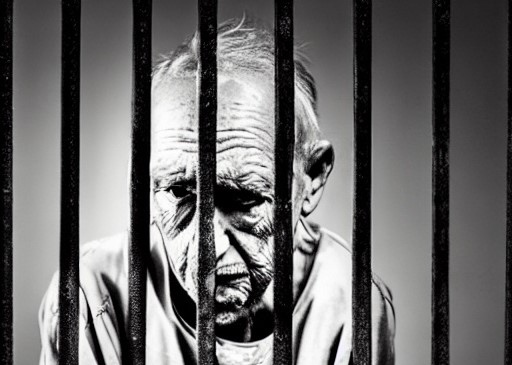

The image of Tata Seló gripping the bars in his confinement carries a dual symbolism, reflecting both physical and metaphorical imprisonment. Physically, the bars represent the oppressive constraints placed on him by a society riddled with economic inequality and injustice. He finds himself trapped in a cycle of poverty and powerlessness, unable to break free from these societal and economic forces. Metaphorically, these bars encapsulate the larger theme of confinement in the story – not only the literal bars of a cell but the invisible barriers that restrict the opportunities and aspirations of those on the margins of society.

Literary Techniques Used

Dialogue: The use of dialogue is prominent, offering insights into the characters' emotions, conflicts, and perspectives. It provides a direct expression of the tensions and power dynamics within the narrative.

Foreshadowing: Elements like the arrival of the authorities and the reactions of the characters foreshadow the unfolding tragedy, creating suspense and tension.

Morning in Nagrebcan

by Manuel E. Arguilla

Reflection

"Morning in Nagrebcan," a poignant story offers a reflective glimpse into the simplicity and harshness of rural life. The hardness of life in Nagrebcan is made clear as the plot develops as the characters toil endlessly in the fields to make poor ends meet.

These problems highlight the tenacity and toughness needed to endure in such a situation. Nevertheless, despite the difficulties, the author also illustrates the strong familial ties that exist, highlighting the love and camaraderie shared by residents of the barrio. In this sense, "Morning in Nagrebcan" celebrates the strength of human bonds and the tenacious spirit of its protagonists as well as illustrating the difficulties of rural living.

Themes & Cultural Context

Family Dynamics: The story explores the relationships within a family, particularly the interactions between siblings and the challenges posed by an authoritarian father.

Cruelty and Violence: The narrative exposes the harshness of the father, Tang Ciaco, who resorts to violence not only towards the puppies but also towards his own children, portraying a darker side of family life.

Symbolism

The litter of puppies symbolizes innocence and vulnerability. The black-spotted puppy becomes a focal point of conflict and tragedy, representing the fragility of life. Tang Ciaco's use of firewood as a weapon becomes a symbol of his dominance and cruelty. It signifies the destructive power he wields over his family.

Literary Techniques Used

Dialogue: The dialogue captures the tone of familial interactions, revealing both the tenderness and the harshness in the characters' relationships.

Foreshadowing: The author hints at the impending tragedy through subtle cues, building suspense and tension as the narrative unfolds.